I mention writing and reading rhythms in Toing and Froing Again Parts 2 and 3 and mentioned in other posts readers often tell me my writing pulls them along, that reading my work is effortless because it flows. First reader and critique group comments are often along the lines of “These lines flow so well and are easy to picture.” with criticisms along the lines of “this part broke the flow of the scene for me.”

There’s (hopefully) no effort reading my work because I write to a rhythm which is what readers describe as “flow.” That rhythm depends on the work itself. Some pieces are meant to be read at a quick march, some at a slow waltz, some are jive, some are tango. I work at creating a rhythm that non-consciously catches the reader and propels them through whatever they’re reading.

To do that properly – and this is key – I need to write to a rhythm. My writing rhythm differs from the reading rhythm in beats (in music, per minute. In writing, per line, paragraph, scene, …), not in time signature (in music, 2/3, 3/4, 7/8. In writing, which beats are emphasized. Study the music of James Brown. He mastered playing to the beat). Most writers/authors change time signatures via chapter breaks, scene breaks, page breaks, et cetera. Ever write an action scene and have a character pause at the end? Congrats, you’ve changed the time signature. Does the pause carry a different number of beats than the action sequence? Probably better if you have a complete break.

Writing and reading rhythms differ because I compose more slowly than I play. Two things one learns in music – sight-reading and improvisation – come in writing and usually after lots of practice (for me, anyway).

Sight-reading occurs when I write to an outline; all the pieces are there and I’m adding the flourish, the emotion, essentially turning the outline into a story. Improvisation happens when I have the basic idea and I sit down and write without an outline. The two are the dividing line between pantsers and plotters. Sight-reading is plotting and improvisation is pantsing.

Consider the following from Writing Realistic Hand-to-Hand Combat Scenes

Ellie blocked Earl’s left with her right. She locked his wrist and elbow against her abdomen. Her elbow smashed his ribs. He coughed up blood. A hammerfist to the groin doubled him over. A front knee strike shattered his jaw. He fell and she released his arm. He wasn’t getting up again.

Pay attention to how you read that excerpt and you may notice a change when you hit “He wasn’t getting up again.” I changed the time signature so the reader could catch their breath after an action sequence. I do such things because I want the reader to relate strongly to the character. If the character can relax, I want the reader to do the same.

However, I can’t write at a tango rhythm if I want the reader to move at a jive rhythm. I can slow the jive down but too much and it’s no longer jive, it’s jibberish.

Take another look at the Writing Realistic Hand-to-Hand Combat Scenes excerpt:

- Ellie blocked… – Strong simple past tense verb two beats in (second word in sentence)

- She locked… – Ditto

- Her elbow smashed… – Strong simple past tense verb three beats in

- A hammerfist to the groin doubled… – Strong simple past tense verb six beats in

- A front knee strike shattered… – Strong simple past tense verb five beats in

- He fell and she released… – Ditto

- He wasn’t getting up… – Weak, past continuous (or past progressive) tense taking up three beats.

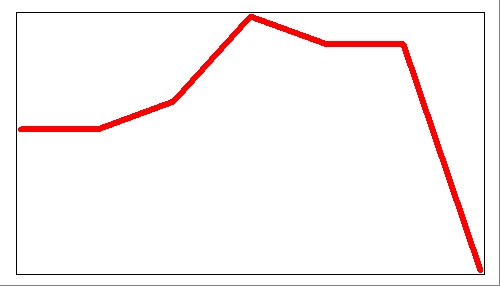

Chart this and you get

Have you ever listened to some music and things suddenly get more intense, more lively, perhaps louder, and next there’s a sudden quiet or slowing down or change in the chord structure? That’s what you’re seeing in the chart above, a kind of crescendo in the writing and done with language instead of music. That sudden drop at the end is the diminuendo and due to a change in verb tense, hence authorial voice, and signals an end to the scene therefore a scene break (as written it would be a good cliff-hanger chapter break, too. Always leave ’em wanting more).

The crossovers between music and writing, writing and photography, dance and writing, … are too numerous to elaborate here. Ask me about them if we’re together in a writing class.

In the meantime, study different disciplines to strengthen your writing. I study photography to learn how to put scenes together. I study acting to learn how to show emotion. I study music to learn how to pace my work. I study artwork to learn how to draw readers’ attention where I want it.

And always practice practice Practice!