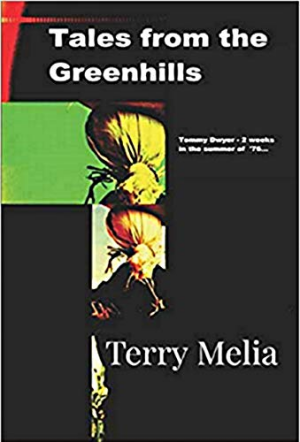

Let me get the obvious out of the way; Bravo, Mr. Melia. Bravo!

Let me get the obvious out of the way; Bravo, Mr. Melia. Bravo!

Now repeat that half a dozen times to get it out of my system.

I completed my third read of Tales from the Greenhills less than fifteen minutes ago. It’s going on my reread shelf.

One of my unwritten rules for realizing a book is stunning is getting to the end and wanting the story to continue, to find out what happens next to the characters (Melia says sequels are in the works. I’m holding him to that).

Another unwritten rule is having the characters sneak up on you such that you don’t realize you’re vested in their lives more than your own, that you care about them as people, not as characters in a story.

Bravo, Mr. Melia! Bravo!

American readers may have trouble with the language. Remember the first time you saw The Full Monty or Waking Ned Devine? You wanted subtitles for the first ten minutes until you got use to the accents? I had a similar experience reading the dialogue for the first time. I reread sentences to make sure I got the meanings correctly. Once I accepted the vernacular, I realized it was perfect.

Let me focus on that “perfect” part. Future anthropologists will pick up Tales from the Greenhills and realize they have a textbook for late 1970’s Liverpool, England, and the world. This book is so rich with cultural iconography is could be used as a time traveler’s guide to time and place.

Tales from the Greenhills is also a coming-of-age story meets Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, although I didn’t recognize this until half way through my second read and realized fully during my third read. Regarding the Hero’s Journey aspect, Melia couldn’t have done a better job of placing Le Queste de Saint Graal in modern England if he tried (don’t tell him I said that. He’ll prove me wrong and do it). It’s all there and I laughed when I finally recognized the separate characters for their Journey counterparts.

Again and again and again, Bravo, Mr. Melia! Bravo!

Do you need to read it three times to appreciate it? No, not at all. However, if you’re an author or writer-wannabe you must read this novel multiple times. Melia does an amazing job with scenes, characterization, mood, place, setting, voice, POV…I need to know this was by accident. If Melia set out to produce this rich a story, I’m going to hang up my writing shifts now, I can’t compete.

I did have the privilege of exchanging comments with Melia during my reading. His attention to detail — this is a movie or should be – think Trainspotting meets Oliver’s Travels — caused me to ask how much was imagined and how much remembered. I won’t give away his answer except that it increased my respect for both him and his work.

The book is also rich in quotable lines; “the only thing money can’t buy is poverty.” If Melia lifted that — good authors borrow, great authors steal — please tell me where so I can play in the treasure.

And last note; the opening scene. The book opens literally with the aftermath of the story. Not the conclusion, the aftermath of the climax. Brilliant, brilliant, brilliant! As I learned to say in Glasgow, “Pure Dead Brilliant, Jonnie!” Get past the first chapter and the rest of the book builds moment by moment, scene by scene, to the climax. You know it’s coming — you’ve already read the aftermath — and Melia keeps notching up the tension for what you already know is going to happen.

Again, Brilliant, Brilliant, Brilliant.

Okay, the for real last note; the last three paragraphs. I read them and laughed. Oh, Mr. Melia, BRAVO!

Minor technical matters for American audiences

Editing styles in the UK differ slightly from their US counterparts. Some constructions don’t roll smoothly off the American tongue. They’re awkward, not confusing, much like I wrote above regarding dialogue.

I took them as an opportunity to increase my understanding of contemporary British literature and hope I’m a better all-around reader for it.